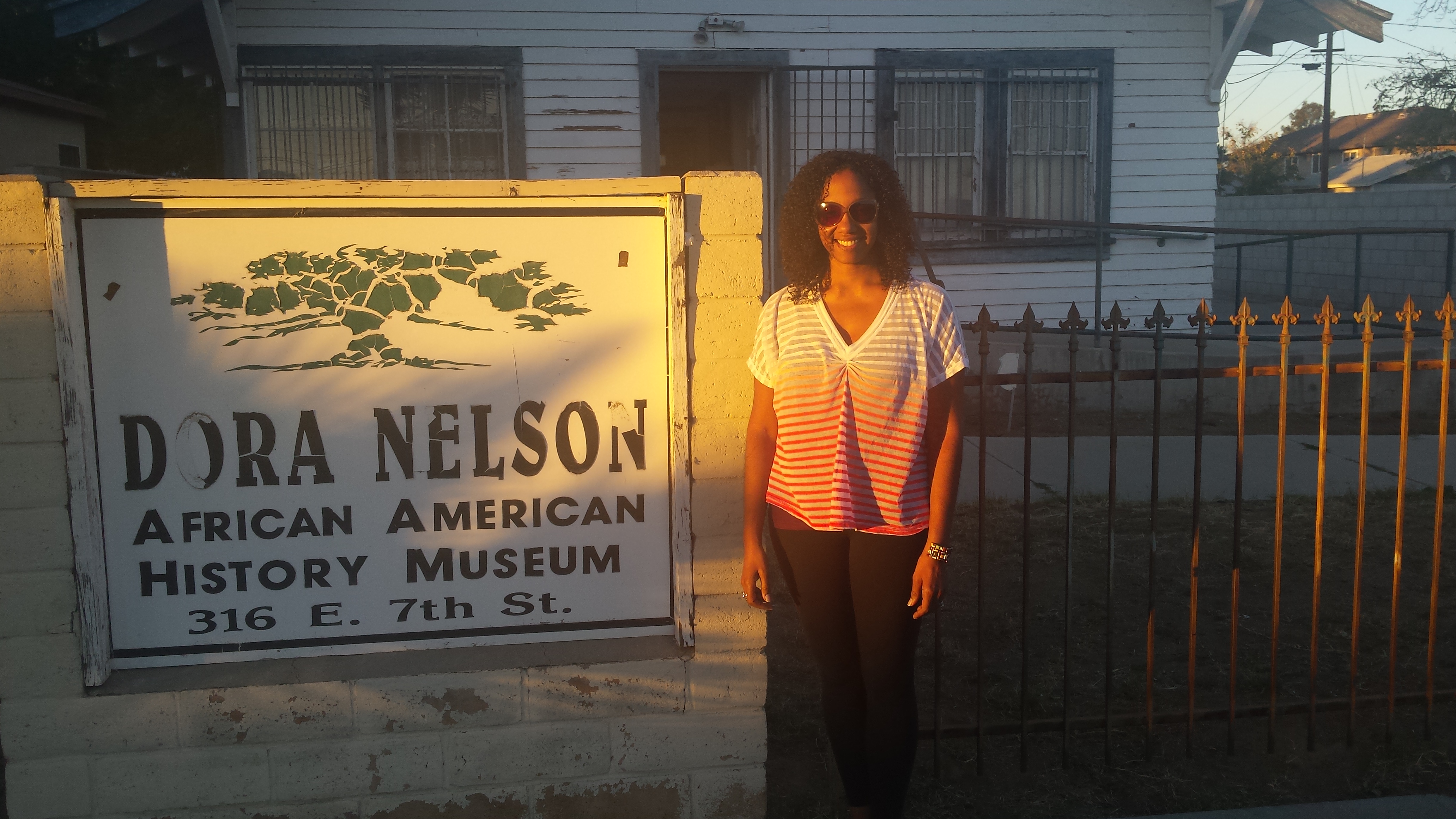

Dora Nelson African-American Art & History Museum

Perris, California (Free)

November 13, 2015

I first met Lovella Singer, the executive manager of the Dora Nelson African-American Art & History Museum, in Memphis at the 2015 Association for African-American Museums Conference. I was overjoyed to discover that the 2016 conference would be held in Riverside, local for me, hosted by the Dora Nelson Museum. I heard bits and pieces about the museum from Lovella in Memphis, but I determined that I would need to pay a visit to this hosting museum before the conference to get the full story.

The museum is intended to provide information about the history of the African-American community in Perris where Dora Nelson settled in 1920 and Lovella’s own mother, Alberta Mable Kearney, the now 95-year-old granddaughter of a slave, settled later with her husband and eleven children on the same block where Dora Nelson had lived.

The museum is intended to provide information about the history of the African-American community in Perris where Dora Nelson settled in 1920 and Lovella’s own mother, Alberta Mable Kearney, the now 95-year-old granddaughter of a slave, settled later with her husband and eleven children on the same block where Dora Nelson had lived.

The women tell the dramatic tale of Mrs. Kearney being offered money to demolish an old home on her block in the Perris neighborhood where she had recently moved. Eager for the opportunity to earn extra cash and admiring the doors on the home, Mrs. Kearny put her children to work pulling down the house brick by brick. She had her eye on the doors, and when they had completed the job, she retrieved those doors with the intent of using them for her own home. However, when a neighbor informed her that her family had just demolished the home that had served as the first place of worship for Black families in Perris, Mrs. Kearney was devastated. She eventually committed herself to learning the history of the African-American community in Perris and honoring that history in a significant way.

The women tell the dramatic tale of Mrs. Kearney being offered money to demolish an old home on her block in the Perris neighborhood where she had recently moved. Eager for the opportunity to earn extra cash and admiring the doors on the home, Mrs. Kearny put her children to work pulling down the house brick by brick. She had her eye on the doors, and when they had completed the job, she retrieved those doors with the intent of using them for her own home. However, when a neighbor informed her that her family had just demolished the home that had served as the first place of worship for Black families in Perris, Mrs. Kearney was devastated. She eventually committed herself to learning the history of the African-American community in Perris and honoring that history in a significant way.

In 1979, Mr. and Mrs. Kearny decided to found a museum and donate the land where their family home had once stood for that purpose. That is where the Dora Nelson Museum of African American Art and History now stands.

The day I visited the museum, I was fortunate to meet Mrs. Kearny who is a wealth of wisdom. She shared memories of the old house that had once stood on that same spot. She shared that the house had been built of rejected lumber because good lumber was reserved for World War II construction. She remembered how the house fell apart, literally into the family’s food. She and Lovella remembered how, to the children’s chagrin, a beam fell into a giant pot of beans Mrs. Kearny had been cooking for hours. Mrs. Kearny also explained to me the background of one of the museum’s focal exhibits, the Step Up and Be Counted Shoe Collection, a unique exhibit where they display the shoes of individuals from the community who, as Mrs. Kearny put it, “excelled in the area of human relations.” One is a former Perris mayor who treated all Perris residents equally, across racial lines. She remembers him running a local store and crediting her children for their shoes when the family could not afford to pay all at once.

The day I visited the museum, I was fortunate to meet Mrs. Kearny who is a wealth of wisdom. She shared memories of the old house that had once stood on that same spot. She shared that the house had been built of rejected lumber because good lumber was reserved for World War II construction. She remembered how the house fell apart, literally into the family’s food. She and Lovella remembered how, to the children’s chagrin, a beam fell into a giant pot of beans Mrs. Kearny had been cooking for hours. Mrs. Kearny also explained to me the background of one of the museum’s focal exhibits, the Step Up and Be Counted Shoe Collection, a unique exhibit where they display the shoes of individuals from the community who, as Mrs. Kearny put it, “excelled in the area of human relations.” One is a former Perris mayor who treated all Perris residents equally, across racial lines. She remembers him running a local store and crediting her children for their shoes when the family could not afford to pay all at once.

Other artifacts around the museum include an iron pot owned by Mrs. Kearney’s late slave grandmother, a photograph of Dora Nelson’s daughter, pairs of original slave shackles, Native American statues and artwork, a founders list, and one of the doors that serendipitously brought together Mrs. Kearney and Dora Nelson.

Other artifacts around the museum include an iron pot owned by Mrs. Kearney’s late slave grandmother, a photograph of Dora Nelson’s daughter, pairs of original slave shackles, Native American statues and artwork, a founders list, and one of the doors that serendipitously brought together Mrs. Kearney and Dora Nelson.

I am eager to watch the museum shape up in the coming months as the team prepares for the August conference. They are working hard to secure funds to do some much-needed renovating.

I am eager to watch the museum shape up in the coming months as the team prepares for the August conference. They are working hard to secure funds to do some much-needed renovating.

Before I left for the day, Lovella drove me around the neighborhood to show me landmarks of Perris’s Black community like churches and historic homes. She explained that after Dora Nelson hosted prayer meetings in her home for years, the male pastors came and got credit for officially starting First Baptist Church, which is now in its third iteration. While Dora Nelson may not have gotten credit from her contemporaries for her leadership, Mrs. Kearney and Lovella are committed that through their museum, Dora Nelson will finally gain the notoriety and recognition she deserves.

Check back next week to read about my visit to the LA County Museum of Art’s Noah Purifoy exhibit: Junk Dada.