The Whitney Plantation

Wallace, LA ($22)

April 2, 2017

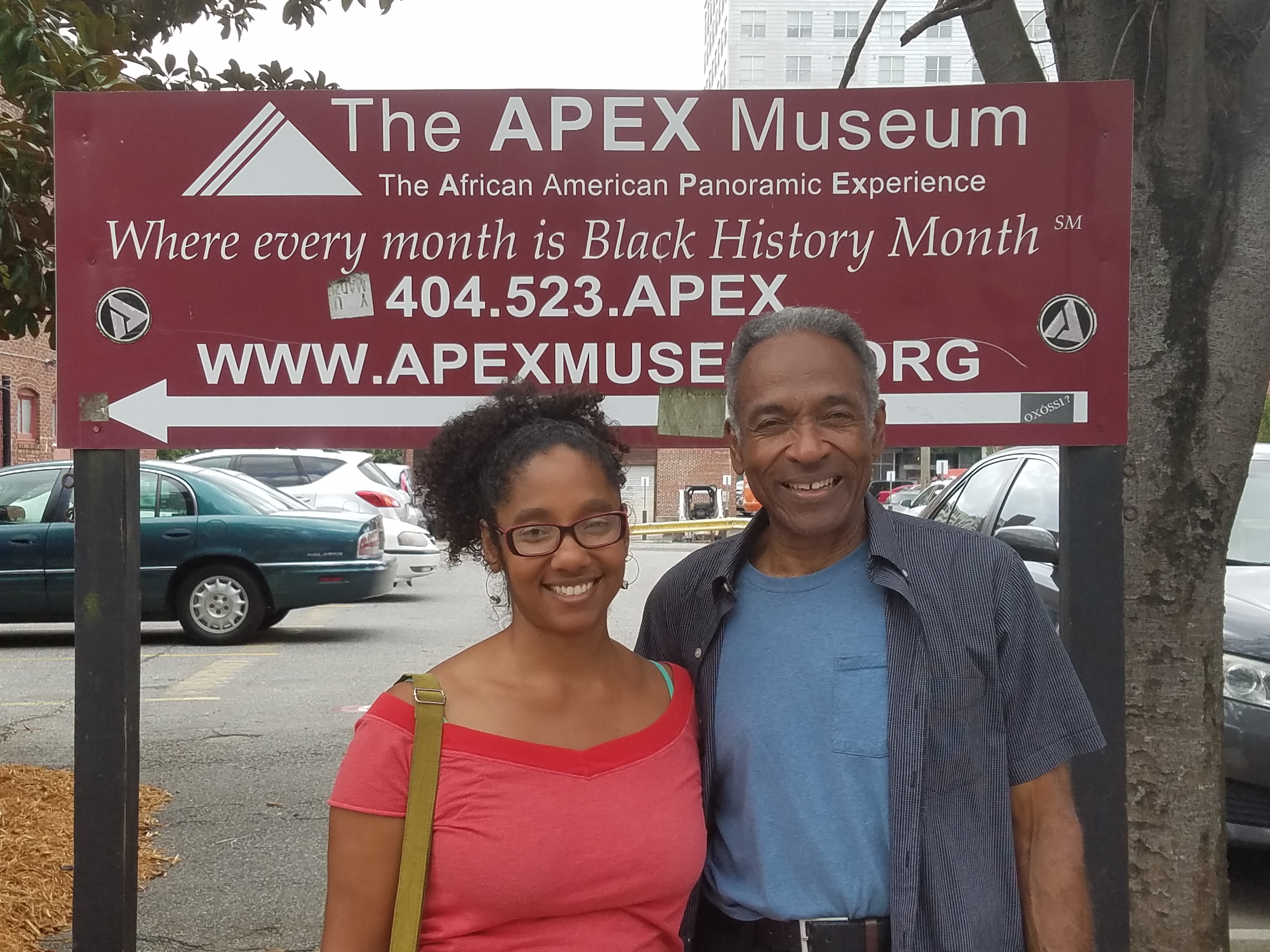

I first read about the Whitney Plantation in a 2015 Los Angeles Times article, which I posted on my Facebook page and started strategizing how I might get there. With two years of anticipation, I was not disappointed. When we arrived, I was impressed by the crowds, the gift shop’s display panels offering an overview of the slave trades, and the diversely stocked gift shop. We arrived around 12:30 on a Monday, and the 1:00 tour was fully booked. Fortunately, a tour group from New Orleans was scheduled to arrive for a 1:15 tour, and we were able to join that group. After Kathe Hambrick, the founder, and director of the River Road African-American Museum, complained of so few visitors and so little funding two days earlier, I considered why this plantation, about the same distance from New Orleans as the River Road Museum, is bursting with visitors willing to pay $22 admission. The very different circumstances of its founding likely explain the disparity.

The Whitney Plantation was purchased by John Cummings, a white New Orleans lawyer, in the 1990’s, and it is well-known for being the only Louisiana plantation with a focus on its enslaved residents. I remember visiting plantations that were tourist destinations on a family vacation in the Caribbean and my mother’s grumbling about the lack of recognition of the enslaved people who lived there. Instead of opening that type of tourist destination, Cummings hired

The Whitney Plantation was purchased by John Cummings, a white New Orleans lawyer, in the 1990’s, and it is well-known for being the only Louisiana plantation with a focus on its enslaved residents. I remember visiting plantations that were tourist destinations on a family vacation in the Caribbean and my mother’s grumbling about the lack of recognition of the enslaved people who lived there. Instead of opening that type of tourist destination, Cummings hired

Senegalese historian Ibrahim Seck and venture into this uncharted territory and as a result, the Whitney has gotten a wealth of publicity, including that full-page write-up in the Los Angeles Times, and NPR story. Cummings was also able to invest millions of dollars of his own money into the Plantation, which is not an option for most small Black museum founders.

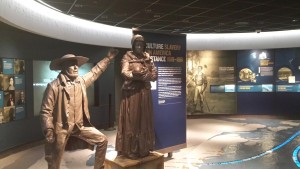

Yvonne from Chicago was our tour guide, and she explained the history of the plantation. The tour began in a church that had been brought onto the property, and she explained that Black churches founded around the middle of the 19th century labeled themselves “anti-yoke” to express their anti-slavery stance, which eventually became “Antioch.” In the church are statues, carved by Woodrow Nash, of enslaved children intended to honor the people interviewed during the WPA’s 1930s project where formerly enslaved individuals were interviewed. Those subjects had all been children when those enslaved in America were emancipated.

I was surprised to see that the plantation contains several sizeable monuments to enslaved people. The first one we visited was the one dedicated to the enslaved people who lived on the plantation, with the names of the over 350 enslaved people engraved into granite slabs. Then, a much larger monument lists the names of 107,000 people held in bondage in Louisiana between 1719 and 1820. Then, the most heart-wrenching monument for me was the Field of Angels listing names of 2200 enslaved infants who died in St John the Baptist parish.

I was surprised to see that the plantation contains several sizeable monuments to enslaved people. The first one we visited was the one dedicated to the enslaved people who lived on the plantation, with the names of the over 350 enslaved people engraved into granite slabs. Then, a much larger monument lists the names of 107,000 people held in bondage in Louisiana between 1719 and 1820. Then, the most heart-wrenching monument for me was the Field of Angels listing names of 2200 enslaved infants who died in St John the Baptist parish.

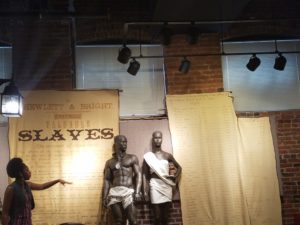

We also visited a few structures on the site including a slave cabin, a jail, a blacksmith shop, and the big house. Yvonne encouraged us to visit the “optional” exhibit on the property dedicated to the participants of the 1811 German Coast Uprising. The uprising was quelled and the participants were executed. Many of them were decapitated and their heads placed on display on stakes as warnings to other slaves. An artist’s rendering of the heads on stakes along with panels describing the uprising can be found in the back corner of the plantation available to interested visitors.

We also visited a few structures on the site including a slave cabin, a jail, a blacksmith shop, and the big house. Yvonne encouraged us to visit the “optional” exhibit on the property dedicated to the participants of the 1811 German Coast Uprising. The uprising was quelled and the participants were executed. Many of them were decapitated and their heads placed on display on stakes as warnings to other slaves. An artist’s rendering of the heads on stakes along with panels describing the uprising can be found in the back corner of the plantation available to interested visitors.

The Whitney Plantation is well-funded and impressive. It fills a niche nicely and draws visitors from around the world to expose them, not just to the horrors of slavery, but also to the humanity of people who were enslaved. I know that some in the Black museums community are frustrated by the fact that Cummings, because of his access to resources, has had the privilege to tell this part of “our” story while many of us, even those who are museum professionals, cannot have his reach.

The Whitney Plantation is well-funded and impressive. It fills a niche nicely and draws visitors from around the world to expose them, not just to the horrors of slavery, but also to the humanity of people who were enslaved. I know that some in the Black museums community are frustrated by the fact that Cummings, because of his access to resources, has had the privilege to tell this part of “our” story while many of us, even those who are museum professionals, cannot have his reach.

Check back to read about my visit to New Orleans’s George and Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art.

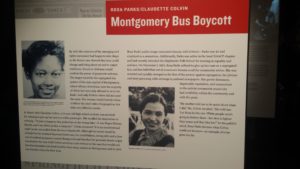

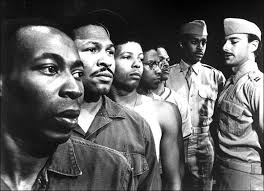

As I walked through this museum, naturally, many of the exhibits reminded me of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute: Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, the freedom riders’ bus, King’s prison cell, etc. However, this museum has one extensive exhibit that recognizes an element of the Movement that I do not remember seeing in Birmingham:

As I walked through this museum, naturally, many of the exhibits reminded me of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute: Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, the freedom riders’ bus, King’s prison cell, etc. However, this museum has one extensive exhibit that recognizes an element of the Movement that I do not remember seeing in Birmingham:

What stood out most to me was Carver’s educational innovation. He implemented distance learning before the Internet and television. He designed the

What stood out most to me was Carver’s educational innovation. He implemented distance learning before the Internet and television. He designed the

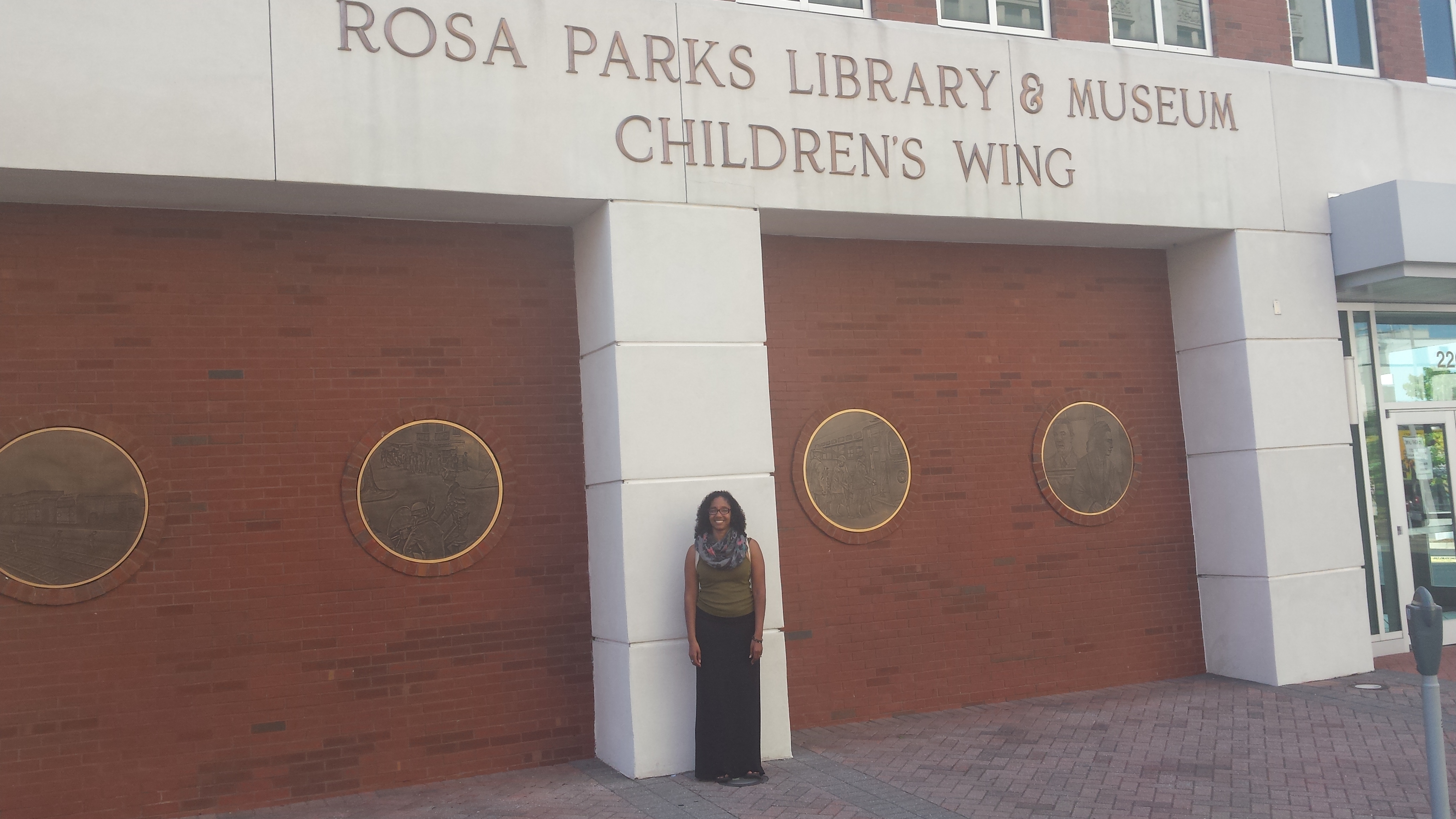

The museum is separated into two wings, a Children’s Wing and the main museum. The exhibits have been the same since 2000, so the new director, Felicia Bell, is eager to replace them with more updated and interactive displays. I found them highly original, especially the kids’ exhibit, which uses the premise of time travel. In the lobby a schedule of the time machine’s travel is posted along with an explanation of how time travel works. In the center of the main exhibit room is a rocking and rolling bus “time machine” on which passengers travel to the time before the Civil War and learn about Dred Scott, his family, and their great loss in the Supreme Court with a video that includes actual photographs along with some reenactment. We also learned the origins of the term “Jim Crow”.

The museum is separated into two wings, a Children’s Wing and the main museum. The exhibits have been the same since 2000, so the new director, Felicia Bell, is eager to replace them with more updated and interactive displays. I found them highly original, especially the kids’ exhibit, which uses the premise of time travel. In the lobby a schedule of the time machine’s travel is posted along with an explanation of how time travel works. In the center of the main exhibit room is a rocking and rolling bus “time machine” on which passengers travel to the time before the Civil War and learn about Dred Scott, his family, and their great loss in the Supreme Court with a video that includes actual photographs along with some reenactment. We also learned the origins of the term “Jim Crow”.

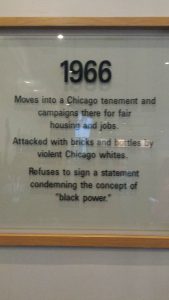

Of course, 27-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. is featured in the exhibit as the leader of the boycott. I had no idea that he and other leaders did not initially ask for the complete elimination of segregation, even on Montgomery busses. The protesters were only asking that Black passengers be treated with as much respect as White passengers, even if they remained segregated. They also requested that the bus company hire African-American drivers to drive in African-American neighborhoods.

Of course, 27-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. is featured in the exhibit as the leader of the boycott. I had no idea that he and other leaders did not initially ask for the complete elimination of segregation, even on Montgomery busses. The protesters were only asking that Black passengers be treated with as much respect as White passengers, even if they remained segregated. They also requested that the bus company hire African-American drivers to drive in African-American neighborhoods.

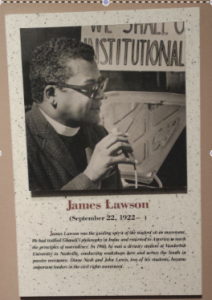

t stood out most to me in this museum was of a personal nature, two photographs and descriptions of the Reverend James Lawson’s role in the Movement are included in this gallery. I grew up hearing James Lawson’s sermons, and he officiated my wedding, so seeing him recognized always gratifies me.

t stood out most to me in this museum was of a personal nature, two photographs and descriptions of the Reverend James Lawson’s role in the Movement are included in this gallery. I grew up hearing James Lawson’s sermons, and he officiated my wedding, so seeing him recognized always gratifies me.

After fully exploring the ground floor of the museum, we opted to break for lunch, especially since the youngest member of our party, five-year-old, Kyler, had expressed a desire to eat. One of the friendly employees gave us a map of downtown Macon and offered a few recommendations. We ended up at Market City Cafe, where the really standout item was the delicious fried string beans. The four adults devoured two full orders. (Kyler wasn’t interested.) The sweet tea wasn’t half bad, and nobody complained about the red velvet cake either.

After fully exploring the ground floor of the museum, we opted to break for lunch, especially since the youngest member of our party, five-year-old, Kyler, had expressed a desire to eat. One of the friendly employees gave us a map of downtown Macon and offered a few recommendations. We ended up at Market City Cafe, where the really standout item was the delicious fried string beans. The four adults devoured two full orders. (Kyler wasn’t interested.) The sweet tea wasn’t half bad, and nobody complained about the red velvet cake either.

We arrived for only about the last two hours of the Jubilee, so we missed most of the scheduled activities like the tug of war, the foxtrot lessons, and the cakewalk held in various locations around the park. We went into the temporary Visitors Center first, signed in and noticed the map showing where previous visitors had come from. Next, we entered the schoolhouse, which, it turned out, was the second one built in the town and was initially led by William Payne. In it were set up period desks, an old typewriter, and other furniture. A docent in that building offered information about its history.

We arrived for only about the last two hours of the Jubilee, so we missed most of the scheduled activities like the tug of war, the foxtrot lessons, and the cakewalk held in various locations around the park. We went into the temporary Visitors Center first, signed in and noticed the map showing where previous visitors had come from. Next, we entered the schoolhouse, which, it turned out, was the second one built in the town and was initially led by William Payne. In it were set up period desks, an old typewriter, and other furniture. A docent in that building offered information about its history.

We moved on to walk around the town visiting the buildings like the library; the Scott-Gross drug store, where we met Shirley Collins and Fannie Franklin making button spinner toys for kids; and the Singleton General Store where we saw the original ice box and bulk items display case. We also passed a barber shop; the Smith house, which is rumored to be haunted; the hotel; a couple of other stores; a boarding house; a railroad car; and a bakery.

We moved on to walk around the town visiting the buildings like the library; the Scott-Gross drug store, where we met Shirley Collins and Fannie Franklin making button spinner toys for kids; and the Singleton General Store where we saw the original ice box and bulk items display case. We also passed a barber shop; the Smith house, which is rumored to be haunted; the hotel; a couple of other stores; a boarding house; a railroad car; and a bakery.

Like the

Like the

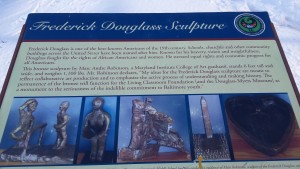

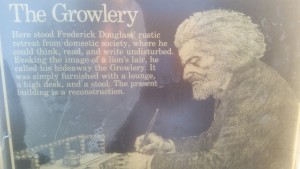

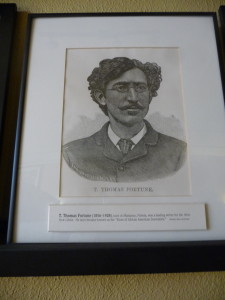

I was also surprised to learn through his exhibit that the US Navy was not segregated, and African-Americans had been serving in the Navy for decades before the Civil War. This explains Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery wearing a sailor suit, which was not an uncommon sight at the time. The numbers of

I was also surprised to learn through his exhibit that the US Navy was not segregated, and African-Americans had been serving in the Navy for decades before the Civil War. This explains Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery wearing a sailor suit, which was not an uncommon sight at the time. The numbers of

End of American Slavery.

End of American Slavery.

This museum was such a pleasant surprise, not on my itinerary but an important

This museum was such a pleasant surprise, not on my itinerary but an important

This museum houses a temporary exhibit on the second floor, and when I visited, the exhibit was

This museum houses a temporary exhibit on the second floor, and when I visited, the exhibit was  There is an exhibit honoring the role of the barbershop in the Black community. There is a powerful small room shaped like a tree trunk in which visitors can and read the names of lynching victims projected on the wall and hear their names read. There is an exhibit showing the role of slave labor in cultivating tobacco in the region. There is a description of the ships built in Baltimore shipyards that were used to transport human cargo. There is an entire wing focused on African-Americans’ historic relationship with Baltimore’s maritime industry. I was introduced to early feminist abolitionists like

There is an exhibit honoring the role of the barbershop in the Black community. There is a powerful small room shaped like a tree trunk in which visitors can and read the names of lynching victims projected on the wall and hear their names read. There is an exhibit showing the role of slave labor in cultivating tobacco in the region. There is a description of the ships built in Baltimore shipyards that were used to transport human cargo. There is an entire wing focused on African-Americans’ historic relationship with Baltimore’s maritime industry. I was introduced to early feminist abolitionists like

After recovering from the

After recovering from the  Back down on the main floor of the museum, the last section to see before you exit is Main Exhibit Hall #2. As you enter that section of the museum,

Back down on the main floor of the museum, the last section to see before you exit is Main Exhibit Hall #2. As you enter that section of the museum,

d the HBO series, The Wire, but I am sure The Great Blacks in Wax Museum is located right in the middle of the set for that show. The museum opened in the 1980s in a converted fire station, which has afforded it extensive square footage for exhibits. We were greeted in the foyer of the museum by wax figures of

d the HBO series, The Wire, but I am sure The Great Blacks in Wax Museum is located right in the middle of the set for that show. The museum opened in the 1980s in a converted fire station, which has afforded it extensive square footage for exhibits. We were greeted in the foyer of the museum by wax figures of  After each visitor bought a ticket, the woman in the Plexiglas-enclosed ticket booth was sure to tell him or her to enter the first exhibit through the red, black, and green swinging doors to her right and start the self-guided tour with

After each visitor bought a ticket, the woman in the Plexiglas-enclosed ticket booth was sure to tell him or her to enter the first exhibit through the red, black, and green swinging doors to her right and start the self-guided tour with

There, Rosemary explained that the home had three bedrooms on the third floor that had been available to traveling African-American women who needed accommodations since accommodations were not readily available to African-American travelers during Bethune’s time. Hanging in Bethune’s room are photographs from her early life including a portrait of her parents, a photograph of Booker T. Washington, a

There, Rosemary explained that the home had three bedrooms on the third floor that had been available to traveling African-American women who needed accommodations since accommodations were not readily available to African-American travelers during Bethune’s time. Hanging in Bethune’s room are photographs from her early life including a portrait of her parents, a photograph of Booker T. Washington, a  Bethune’s office next door still contains the original office furniture, and on display are photos from Bethune’s political life, like one of her in a large group with President Franklin Roosevelt. Rosemary also took us into the conferenceroom that still houses the original wooden conference table and chairs. In that room was also an exhibit, “Bethune Goes to Hollywood,” highlighting Bethune’s relationship with entertainers like

Bethune’s office next door still contains the original office furniture, and on display are photos from Bethune’s political life, like one of her in a large group with President Franklin Roosevelt. Rosemary also took us into the conferenceroom that still houses the original wooden conference table and chairs. In that room was also an exhibit, “Bethune Goes to Hollywood,” highlighting Bethune’s relationship with entertainers like

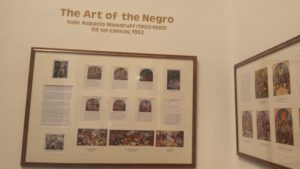

After driving out of the snow falling in Philadelphia, we made our way to the college town of Newark, Delaware. We found the Mechanical Hall Gallery on the University of Delaware campus, which houses the Paul R. Jones Collection of African-American art. The exhibit on display for our visit was

After driving out of the snow falling in Philadelphia, we made our way to the college town of Newark, Delaware. We found the Mechanical Hall Gallery on the University of Delaware campus, which houses the Paul R. Jones Collection of African-American art. The exhibit on display for our visit was

museum is a

museum is a

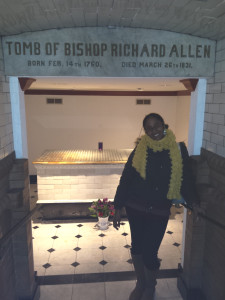

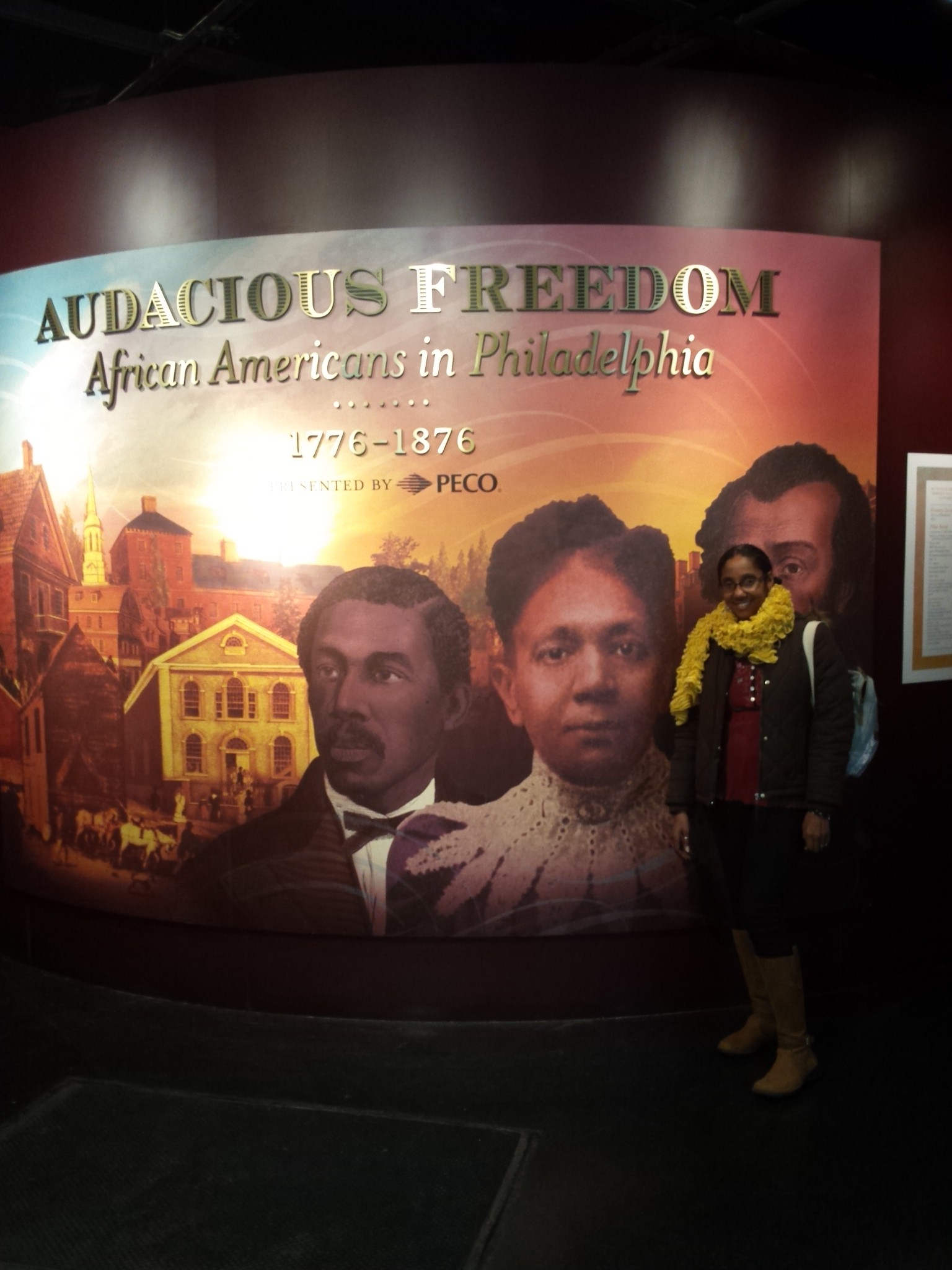

In this gallery are nine human-sized screens positioned inside of window or door frames on which museum visitors see actors playing the important historical figures described in the earlier part of the exhibit like Octavius Catto and Richard Allen telling their own stories. Visitors can press buttons to get certain questions answered by these figures. These displays are certainly like nothing I had ever seen. I can imagine that child visitors are tickled seeing the actors in costume and in character addressing them directly.

In this gallery are nine human-sized screens positioned inside of window or door frames on which museum visitors see actors playing the important historical figures described in the earlier part of the exhibit like Octavius Catto and Richard Allen telling their own stories. Visitors can press buttons to get certain questions answered by these figures. These displays are certainly like nothing I had ever seen. I can imagine that child visitors are tickled seeing the actors in costume and in character addressing them directly. The guide walked with the children to see to Camille Billops’s etching,

The guide walked with the children to see to Camille Billops’s etching,

Once we finished perusing Blackwell’s paintings and learning about Oakland’s Black history, we returned to the first floor where we scanned the library shelves. My sister, herself an artist, discovered some Black art books, and we spent the last of the library’s open minutes exploring the history of African-American art. We were ultimately notified on the library’s loudspeaker that the library was closing. We were the only patrons in the building, so the librarian called us out, expressing his hope that “the two ladies” enjoyed their visit.

Once we finished perusing Blackwell’s paintings and learning about Oakland’s Black history, we returned to the first floor where we scanned the library shelves. My sister, herself an artist, discovered some Black art books, and we spent the last of the library’s open minutes exploring the history of African-American art. We were ultimately notified on the library’s loudspeaker that the library was closing. We were the only patrons in the building, so the librarian called us out, expressing his hope that “the two ladies” enjoyed their visit.

When he opened a dance hall where African-American musicians came from around the country to perform, he realized he would need to provide those entertainers with accommodations too since in the Jim Crow South, hotels owned by Whites would not take Black boarders. Thus, in 1929, he opened the Wells’ Built Hotel. Dr. Wells’ hotel is even listed in 1949 edition of the infamous

When he opened a dance hall where African-American musicians came from around the country to perform, he realized he would need to provide those entertainers with accommodations too since in the Jim Crow South, hotels owned by Whites would not take Black boarders. Thus, in 1929, he opened the Wells’ Built Hotel. Dr. Wells’ hotel is even listed in 1949 edition of the infamous

Our second Florida destination was a small green and white church building in the tiny town of New Smyrna Beach, about fifteen miles from Daytona Beach. I had called ahead and played phone tag with Jimmy Harrell, the executive Director of the museum and widower of Mary Harrell, to ensure that the museum would be open when we arrived.Mr.Harrell was not there on this day; instead, we were greeted enthusiastically by Angie, who is on

Our second Florida destination was a small green and white church building in the tiny town of New Smyrna Beach, about fifteen miles from Daytona Beach. I had called ahead and played phone tag with Jimmy Harrell, the executive Director of the museum and widower of Mary Harrell, to ensure that the museum would be open when we arrived.Mr.Harrell was not there on this day; instead, we were greeted enthusiastically by Angie, who is on  Before we left the museum, they insisted that we tour the Heritage House across the street, a model of a 1920s shotgun house which had been typically inhabited by African-Americans in the community. A variety of relics are on display in theHeritage House including a full kitchen with an old-fashioned icebox, jars of preserved fruits, pots and pans; the bedroom of the Heritage House even has set up an antique typewriter.

Before we left the museum, they insisted that we tour the Heritage House across the street, a model of a 1920s shotgun house which had been typically inhabited by African-Americans in the community. A variety of relics are on display in theHeritage House including a full kitchen with an old-fashioned icebox, jars of preserved fruits, pots and pans; the bedroom of the Heritage House even has set up an antique typewriter.