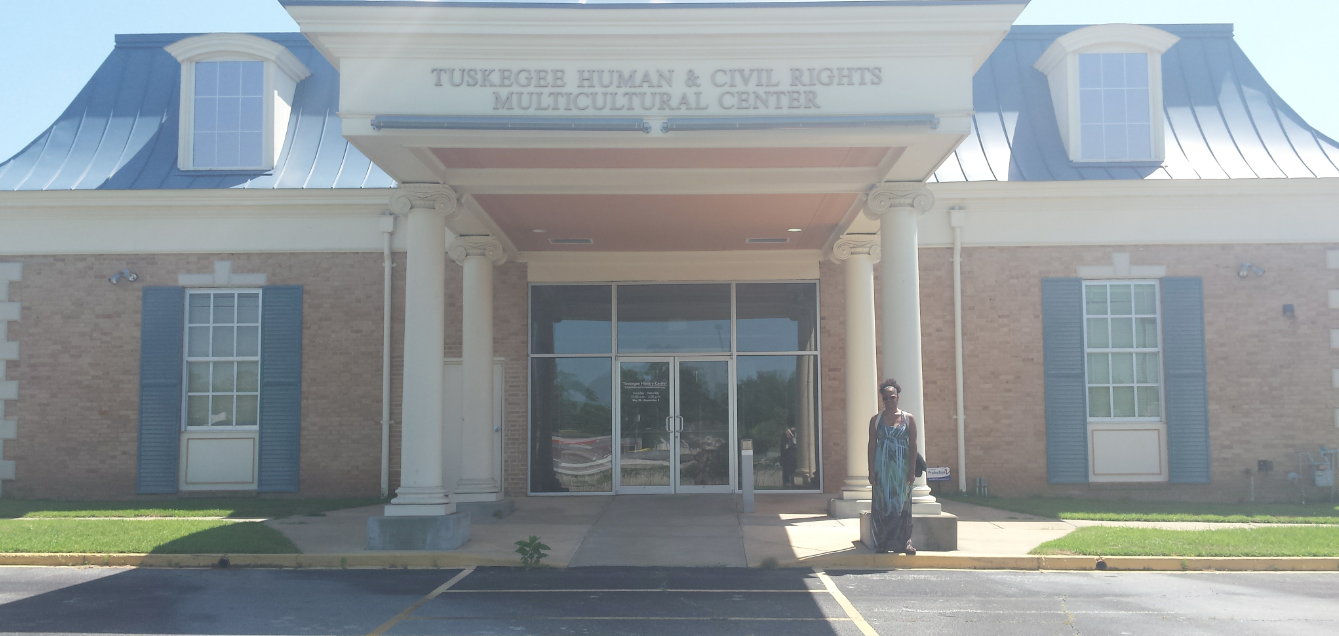

Tuskegee History Center (also Tuskegee Human and Civil Rights Multicultural Center)

Tuskegee, Alabama (Free)

June 16, 2015

This building, which also serves as Tuskegee’s visitor center, is not technically an African-American museum. It is a center focused on the history of the area, and it even dons a logo depicting faces representing the three general ethnic groups present in that history: Native American, African-American, and European-American. Though since Tuskegee’s population is 95.8% African-American and the town houses one of the most famous Historically Black Universities, by default, that ultimately translates into a facility primarily focused on African-American issues.

On the lawn outside the building stands a replica, built in 1957 by the Booker T. Washington Centennial Commission, of Booker T. Washington’s Roanoke, Virginia childhood home. A plaque describes the home using some of Washington’s own words from his book Up from Slavery.

On the lawn outside the building stands a replica, built in 1957 by the Booker T. Washington Centennial Commission, of Booker T. Washington’s Roanoke, Virginia childhood home. A plaque describes the home using some of Washington’s own words from his book Up from Slavery.

The broadest historical exhibit inside of the Center starts with pre-history of the region including what prehistoric creatures lived on the land that is now Macon County thousands of years ago. The exhibit moves on to the humans that first inhabited the area, the Creek people, a matrilineal society, who were ultimately expelled against their will.

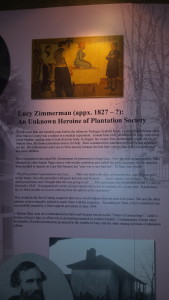

The exhibit moves on to the European migration to the area, and, of course, the accompanying slavery. One small panel that stood out most to my companion for this series of museum visits, my mom, was a description of a slave woman, Lucy Zimmerman, who lived in the area in the early to mid-19th century. A common health problem of the time for women was bladder tearing during childbirth, which lead to ongoing bladder leakage. This slave woman, Lucy, suffered with this condition, and when her master sought treatment for her from Dr. J. Marion Sims, Sims considered her condition untreatable. Then, since her master considered her of no value if she could not bear children, he allowed Sims to keep Lucy. Eventually, Sims acquired other Black women who suffered the same affliction, and he fashioned tools to operate on them. Over the next years, after many experimental operations, he conducted the operations successfully but without anesthesia, and ultimately became world renowned as a result. In the end, these same African-American women, his first, experimental patients, served as his medical assistants. This is just one less-familiar example of the long, complex history of medical exploitation of African-Americans.

The exhibit moves on to the European migration to the area, and, of course, the accompanying slavery. One small panel that stood out most to my companion for this series of museum visits, my mom, was a description of a slave woman, Lucy Zimmerman, who lived in the area in the early to mid-19th century. A common health problem of the time for women was bladder tearing during childbirth, which lead to ongoing bladder leakage. This slave woman, Lucy, suffered with this condition, and when her master sought treatment for her from Dr. J. Marion Sims, Sims considered her condition untreatable. Then, since her master considered her of no value if she could not bear children, he allowed Sims to keep Lucy. Eventually, Sims acquired other Black women who suffered the same affliction, and he fashioned tools to operate on them. Over the next years, after many experimental operations, he conducted the operations successfully but without anesthesia, and ultimately became world renowned as a result. In the end, these same African-American women, his first, experimental patients, served as his medical assistants. This is just one less-familiar example of the long, complex history of medical exploitation of African-Americans.

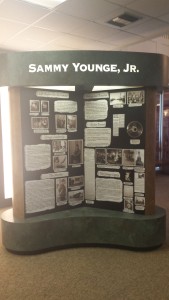

The Center also includes panels describing reconstruction and the dawn of the Jim Crow era along with Civil Rights Movement activities in Tuskegee featuring one martyr of the movement, whom I had never heard of, Sammy Younge, Jr. Younge was murdered in a service station at just 21 years old, shot in the back of the head after an argument with a man who refused to allow him to use the Service Station restroom.

The Center also includes panels describing reconstruction and the dawn of the Jim Crow era along with Civil Rights Movement activities in Tuskegee featuring one martyr of the movement, whom I had never heard of, Sammy Younge, Jr. Younge was murdered in a service station at just 21 years old, shot in the back of the head after an argument with a man who refused to allow him to use the Service Station restroom.

Finally, the Center features an extensive exhibit on the infamous Tuskegee experiment in which approximately 600 African-American men served as research subjects for members of the medical community who wanted to study the effects of syphilis on the body. These men were never told that they had the disease; instead they were told they had “bad blood,” and when penicillin was discovered as a treatment, again, they were not informed, and they were not treated. The preeminent Alabama Civil Rights attorney, Fred Gray, represented the victims in the 1973 class-action lawsuit against the US government. The following year a 10-million settlement was reached. The men are also honored in the Center with their names on floor tiles, and President Clinton’s 1997 apology and his introduction by Herman Shaw, one of the victims, play on a loop in the Center:

On our way out, we chatted with Deborah Gray, Managing Director of the Center. She was a wealth of information about local African-American history, and when we told her we had visited Troy, Alabama, my mom’s birthplace, during our Alabama visit, she lamented the absence of any historical marker recognizing Troy as the birthplace of Civil Rights icon and present-day congressman, John Lewis. Clearly, there is still much work to be done in recognizing African-American history. Fortunately, Tuskegee, Alabama is doing an excellent job.

Check back next Monday to read about my visit to The Oaks, the home of Booker T. Washington on the campus of Tuskegee University.