The Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University

Tuskegee, Alabama (Free)

June 17, 2015

My mom and I arrived at the museum right at 10:00am, the hour it was scheduled to open, but the door was locked. There was a sign saying the museum was “Closed for School Holidays and Breaks,” so we concerned that it might be closed for the summer. However, when I called, we were assured the museum was open, and the woman who answered said she was sending Jeff to let us in.

Jeff gave us a warm welcome and ushered us into the museum’s empty second floor, the art exhibition floor, explaining that we had just missed the P.H. Polk exhibit. They were in the process of preparing that floor for an upcoming art exhibit scheduled to open in the coming fall semester.

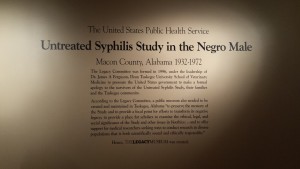

The third floor houses the museum’s permanent exhibits tied to the history of the building as the former John A. Andrew and then John A. Kennedy Memorial Hospital and the current National Center for Research in Bioethics and Health Care. One side houses the exhibit on Henrietta Lacks and HeLa cells, and the other side features the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study we started reading about at the Tuskegee History Center.

The third floor houses the museum’s permanent exhibits tied to the history of the building as the former John A. Andrew and then John A. Kennedy Memorial Hospital and the current National Center for Research in Bioethics and Health Care. One side houses the exhibit on Henrietta Lacks and HeLa cells, and the other side features the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study we started reading about at the Tuskegee History Center.

Jeff offered to give us a tour of the exhibits, and we happily accepted. We started with the HeLa exhibit since I was anticipating reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks later in the summer. Jeff expressed his desire to focus on the contribution Lacks had made to medical research rather than on the injustice of the medical community’s treatment of her and her family. We discussed her cells’ role in the discovery of the Polio vaccine and other medical advancements including HIV and HPV research. He talked about the tours he leads for young students and the connections he makes between the injustices Lacks and her family members suffered and the recent cases of police violence against unarmed Black men caught on film. He observed that the devaluing of African-American lives is at the root of both. We also talked about the partnership between Morehouse School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Tuskegee that is giving students access to extensive cancer and other medical research.

We were running out of time as we got to the exhibit featuring the Tuskegee syphilis study, but Jeff emphasized a point that I had not considered as I learned about the experiment at the previous exhibit: collateral damage. Because the men in the experiment were not informed that they had syphilis, they were allowed to continue to spread the disease throughout their communities without their or their partners’ knowledge. The exhibit is mostly made up of artwork related to the experiments and bioethical issues, and it included a painting by a well-known artist who suffered from syphilis, William Johnson, who also has pieces on display in the Smithsonian.

We were running out of time as we got to the exhibit featuring the Tuskegee syphilis study, but Jeff emphasized a point that I had not considered as I learned about the experiment at the previous exhibit: collateral damage. Because the men in the experiment were not informed that they had syphilis, they were allowed to continue to spread the disease throughout their communities without their or their partners’ knowledge. The exhibit is mostly made up of artwork related to the experiments and bioethical issues, and it included a painting by a well-known artist who suffered from syphilis, William Johnson, who also has pieces on display in the Smithsonian.

Before we left, Jeff lamented a bit to us about challenges with funding for museums and political barriers that plague institutions of higher education. He described the wealth of items in the permanent collection that cannot yet be displayed because they need to be restored and because of spatial limitations in the building. His final words were reassuring, however; he assured us that when we return to the area next summer, the exhibits will be remodeled and refurbished and worth a revisit. We assured him that we would be back!

Before we left, Jeff lamented a bit to us about challenges with funding for museums and political barriers that plague institutions of higher education. He described the wealth of items in the permanent collection that cannot yet be displayed because they need to be restored and because of spatial limitations in the building. His final words were reassuring, however; he assured us that when we return to the area next summer, the exhibits will be remodeled and refurbished and worth a revisit. We assured him that we would be back!

Check back next Monday, September 7th, to read about my visit to the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit, One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works.