Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park

Baltimore, Maryland ($5)

February 20, 2015

This lovely museum is not on the Wikipedia list, but I was telling a colleague who lives in Baltimore about Our Museums, and he reminded me that Frederick Douglass spent much of his childhood in the Baltimore harbor and insisted that I visit the Maritime Park before I left the city.

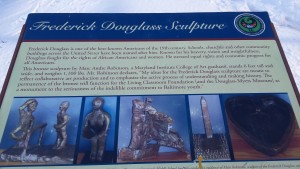

Approaching the museum, there is a lot to see including beautiful views of the harbor and informational signs, but on the winter day when I visited, nothing prepared me for the stunning six-foot bronze memorial bust of Frederick Douglass sitting in front of the building contrasting dramatically with the thin layer of snow on the ground. In the photo I took that day, the statue looks as though one tear has just fallen from Douglass’s left eye. So as I walked into the museum, I wondered what might be causing him to cry. Perhaps he was anticipating the death of Freddie Gray?

The Maritime Park shares space with a few other businesses, and it is three levels with the cashier on the first floor.

The Maritime Park shares space with a few other businesses, and it is three levels with the cashier on the first floor.  Then, the second floor is the screening room for a 20-minute video, which provides extensive background information on the two men and the museum. The second floor includes a few artifacts, panels and other displays. On that floor I learned about the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company, the first African-American owned and operated shipyard in the United States, founded in 1866. Artifacts from the company are on display in the museum along with images of the founders, a group of fifteen middle class African Americans, with expertise in the maritime industry and/or with funds to invest. At the height of its operations, the company employed hundreds of Black and White men and sustained several government contracts.

Then, the second floor is the screening room for a 20-minute video, which provides extensive background information on the two men and the museum. The second floor includes a few artifacts, panels and other displays. On that floor I learned about the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company, the first African-American owned and operated shipyard in the United States, founded in 1866. Artifacts from the company are on display in the museum along with images of the founders, a group of fifteen middle class African Americans, with expertise in the maritime industry and/or with funds to invest. At the height of its operations, the company employed hundreds of Black and White men and sustained several government contracts.

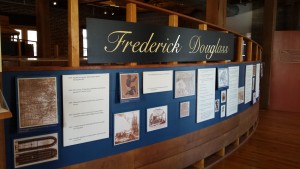

The displays on the third level of the museum detail the personal lives of the two men. This exhibit includes a beautiful wooden replica of a ship skeleton on which artifacts, panels, and images are displayed. Myers, who was new to me, was born free in 1835 and started working as a caulker in the maritime industry in Baltimore when he was sixteen. After the Civil War, he worked to get Black maritime workers organized and started the Colored Caulkers Trade Union Society, which eventually led to the founding of the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company.

After visiting the home where Douglass spent his last years in Anacostia, I was pleased to spend some time in the place where Douglass first gained some independence and eventually escaped slavery. Douglass famously learned to read in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor from White boys in the area with whom he cleverly bartered food for lessons. I learned at this museum about Douglass’s first wife who was free when they met in Baltimore. She took the risk to help Douglass escape slavery and left the city around the same time he did and met him in New York where they were married. The museum includes an exhibit of a mannequin sitting in a train car seat wearing a sailor suit, just as Douglass did to facilitate his escape. Baltimore is so proud of being the town from which Douglass escaped that locals will sometimes lead heritage trail walks in the area that promise to include some of Douglass’s childhood haunts along with various Underground Railroad stops.

This museum was such a pleasant surprise, not on my itinerary but an important Our Museums destination revealing a gross oversight by Wikipedia contributors. I am so thankful to my colleague for making the recommendation.

This museum was such a pleasant surprise, not on my itinerary but an important Our Museums destination revealing a gross oversight by Wikipedia contributors. I am so thankful to my colleague for making the recommendation.

Check back on Monday, June 7th to read about my exploration of the African-American Military Portraits from the American Civil War exhibit at the Los Angeles Central Library.